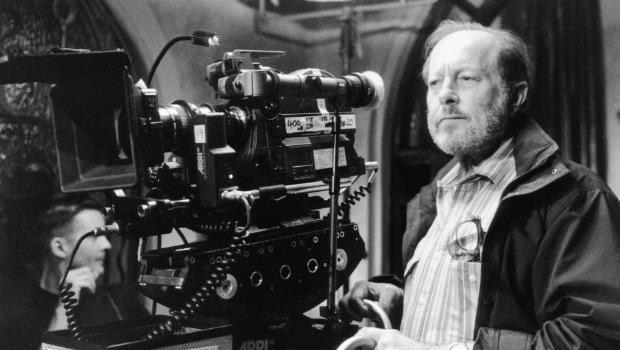

Best British Directors 1: Nicolas Roeg

A filmmaker whose exceptional talent really lay in the creation of intricate and diverse imagery, Roeg is something of a forgotten man in today’s cinematic climate. However he succeeded in contributing a number of highly watchable, interesting and visually articulate movies to the pantheon of great British Filmmaking.

Roeg made his way in the film industry the old fashioned way: through hard graft, starting out in 1947 as an editing apprentice. Working his way up the British cinema hierarchy he got to know many aspects of his craft, eventually rising to the position of cinematographer, where he worked with a range of European cinemas’ leading lights, including François Truffaut (Fahrenheit 451) and John Schlesinger (Far From The Madding Crowd) before he went to make movies in Hollywood. In this respect Roeg was responsible for committing to film some of the most startling and fashionable imagery of the 1960’s that emerged from some of the periods’ most visionary directors.

Despite the fact that Roeg was strictly old school in movies his distinctive outlook sat well with the greater freedom of expression that was sweeping through filmmaking worldwide in the 60s and 70s. His creative preferences tuned in perfectly with the times and this provided him, firstly with his fledgling foray into directing (Performance, 1968) and a concentrated period of success, a success that he has failed to replicate since.

Roegs’ career can be suitably judged in relation to four key films, all rich with characteristic touches, that have been absent in later texts (The Witches for example in the 90’s, we can only assume he had bills to pay!) namely: Performance (co-directed with Donald Cammell), Walkabout, Don’t Look Now and The Man Who Fell To Earth.

A collection of very diverse films that all got the Roeg treatment; they stand as testimony of his virtuoso skill with assembling images in an original way, without interfering too greatly with the narrative. He managed to implement a watered down art cinema aesthetic, replete with non-narrative devices, without alienating the viewer, as the images always remained at least tenuously anchored to some kind of story. This singular viewpoint aroused controversy, particularly amongst studio executives who delayed the release of Performance for 2 years until 1970 because of its “taboo” subject matter and odd delivery. Yet with controversy comes cult success, and in Roeg’s case critical appraisal. He alone seemed to rise above many contemporaries in his ability to take fairly conventional material and invigorate it with a dynamic flair. Roeg would continually use a technique of cross cutting between different scenes and timescales, thus disrupting the conventional visual and temporal order of a narrative, without causing confusion in terms of whats going on. Special visual effects also allowed him to achieve the specific “look” he desired.

Don’t Look Now encapsulates all of Roeg’s filmic pre-occupations, an adaptation of a Daphne Du Maurier ghost story is transposed to the present where Roeg is allowed to do wonders with colour, shadows and light, illuminating the dark side of Venice (where the majority of the action takes place) as a crumbling, cold lump of ornate plaster dissolving into the canals. In The Man Who Fell to Earth, Roeg does for David Bowie what he did for Mick Jagger in Performance. The relative mystery of the narrative and the counter culture leanings of the mis-en-scene perpetuated the myth of the “rock god” that each artist relied upon. Jagger’s bohemian boudoir in Performance was replaced with Bowie’s lost alien sci-fi story, trapped in a world where he doesn’t belong. Roeg knew how to tap into the cult of celebrity that surrounded these figures, and found that it complemented his filmmaking style perfectly.

As the 1970’s dragged on Roeg’s star waned. A creative spirit that was so attuned to a particular epoch became trapped in its replacement. The 1980’s signalled a return to a leaner, less fluid form of expression and Roeg found it increasingly difficult to get his films made, and more importantly distributed. However, he has never stopped working and like his British contemporary Ken Russell, who suffered a similar dip in popularity and is now producing a film in his own home on digital video, continues to probe away on the periphery. Sadly a talent such as Roeg’s has spent far too long in the wilderness, and it seems unlikely that he will ever be allowed to return to the fold. Despite British Cinema’s recent commercial successes we seem to have lost touch with and faith in some of our greatest visionaries, many of whom still have much to offer and pass on. Nicolas Roeg stands at the head of this forgotten group of visionary directors.

Last modified on