Osama Review

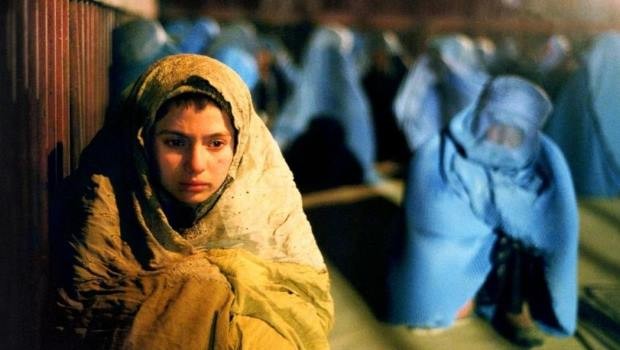

Currently enjoying a lengthy run at every self-respecting arthouse cinema, no one could accuse Siddiq Barmak’s ‘Osama’ – one of the first films to emerge from post-Taliban Afghanistan, and which focuses on the efforts of a young girl (the film’s namesake) to support her mother and grandmother by cutting her hair short and getting employment by pretending to be a boy – of not being topical. But does the film offer anything new or insightful in terms of its representation of a country, a region and a society which has been so heavily demonised by the mass media in recent years?

The film does not start out promisingly. Filmed as it is through the eyes (or camera lens rather) of a Western news journalist, the beginning of the film might almost be considered an oblique comment on the impossibility of getting away from stereotyped images of Afghanistan, and the Middle East in general. The journalist (who is later sentenced to death in the film) is recording a mass rally organised by women, carrying placards and all wearing blue burkas, demanding the right to work. Sooner than you can say ‘bin Laden’, the Taliban have shown up and are beating the women, arresting them, and driving them from the streets by hosing them down with water. The problem with these images (as powerful as they undoubtedly are), as with later images in the film such as the repetitive shots of schoolchildren in class rocking endlessly back and forth and mindlessly reciting the Quran, is that they have become clichés in such a rapidly short space of time, and therefore lack any visceral impact, which is supposedly what the film is striving for.

These clichés however, only serve to highlight those other moments in the narrative when real understanding and originality shine through. These moments are mainly achieved by presenting events via Osama’s subjective point-of-view. From the scene where Osama is forced to climb a tree to prove her ‘manhood’ to a group of boys (when she reaches the top, the jeers of the boys below fade away to show a silent image of Osama balancing precariously on the branches, silhouetted against the sky), to the images of her skipping in her prison cell near the end of the film, and through the chaos of the rally scene at the beginning. These scenes are more than merely “surreal” (as some other reviews have lazily described them), they’re more problematic than that. Arguably the most fascinating scene in the entire film is Osama’s witnessing of the teaching of the ablutions ritual in the boy’s school which she forced to attend, at the risk of revealing her true identity. In this scene we learn that in Afghanistan masculinity, as is the case all over the world, is (in this case literally) a ‘performance’ based upon certain codes and conventions.

The representation of the other non-Taliban male characters in the film is also pleasantly surprising. From the man who helps Osama’s mother avoid the Taliban by pretending to be her husband (ironically only to be berated by the Taliban for letting her talk to strangers!), to the shop-owner who provides work for Osama and plays along with her subterfuge, to the two men sat in the crowd in the film’s penultimate trial scene, who express disapproval at the lack of evidence presented to condemn Osama, the film makes clear that not every man in Afghanistan is an absolute bastard.

The sheer quality of the acting is also worthy of note. Both Marina Golbahari as Osama, and Zubaida Sahar as her mother, are excellent, and almost all the other performances are solid, which came as a surprise to this reviewer, who was expecting another tour-de-force showcase of unconvincing amateur acting.

Barmak received his film training in Iran (and Russia), and it shows. The similarities between ‘Osama’ and any other number of Iranian films produced over the past 25 years are so apparent that it is not worthwhile going into any great detail here. One issue worthy of note however, is the possible (and probable) influence the great Iranian director Mohsen Makhmalbaf, as uncredited producer, had over the proceedings. Indeed, a number of parallels have been drawn between ‘Osama’ and Makhmalbaf’s 2001 film ‘Kandahar’, also set in Afghanistan. For those of you who may have seen ‘Kandahar’, and were completely bemused by the praise heaped upon this portrayal of Afghanistan under the rule of the Taliban, let me assure you that Barmak’s film is infinitely superior to Makhmalbaf’s complete turkey of a movie.

Essential viewing then, but certainly not the masterpiece so many people so desperately want it to be. And on a sidenote, watch out for the Taliban guard who forces Osama to attend the boy’s school, and who eventually discovers her true identity. I can describe him in just five words: Brian Blessed in a turban. Freaky!

Last modified on