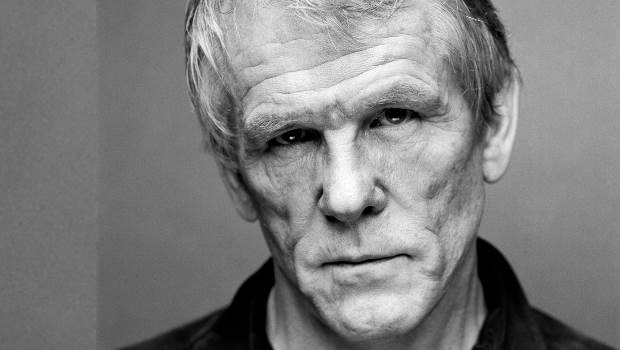

Nick Nolte

How did you get involved in The Good Thief?

Neil Jordan called out of the blue. I was in San Francisco doing Sam Shepard’s play The Late Henry Moss and he sent me the script and I read it. At first I didn’t totally embrace it. What was thawing me off was my own visual and experiential memories of what a heist film is, what a caper film is, what a casino film is. These are lines that have been covered many, many times. Even though my character Bob was an addict in it, I didn’t see necessarily how that interrelated, because I didn’t truly know what a gambler was. I have that quality in me – I am a gambler in a lot of ways, but I didn’t know specifically what it was. So Neil visited and we talked. When I went to dinner to meet Neil I was on crutches!

What had you done?

When I was doing the play, I had an injury to my leg, where the fascia

was ripped and the calf was blown out. I was able to strap the leg up and ice it before I did the first act with Sean Penn. I was off the second act and we’d ice it again. And then I’d go back out and grin and bear it for the third act.

I talked to him a little bit and he discussed the cast, that it would be all European actors, this whole thing, well I got quite excited about it. Then we discussed this expatriate American quality, we discussed gambling, and by the end of the evening I said to Neil, ‘Do you really want to do this? and he said, ‘Yes’, and I said, ‘Well I really want to do it. And then I proceeded to go to work on it. And then I found all these wonderful layers and dimensions to it.’

What does ‘going to work’ on a character involve for you?

It’s a lot to do with his activities. It’s a lot to do with really knowing what a gambler is going after, the aspects of it. We had this good book by Jack Black Money Spinners that discussed the nature of it. They are self-evident things, but you just haven’t thought of it. You haven’t zeroed in on that subject. One of the aspects was that gamblers have trouble with authority. In robbing the casino, they are trying to beat that. That reaches right in to Bob’s connection as a thief, but also his addiction, which is a rebellion against his own personal authority. It’s the low side of him, which is the cascade of experience. Also it’s the fact that he is the age that he is. He’s reached that point of not having the passion. Bob Le Flambeur was one of the first films that had identified criminality and art as having this simpatico relationship. You can understand that in the need for freedom and then all these characters started to become multi-dimensional. What was in Nutsa’s character that sparked him? – was it sexual attraction?, was it beauty?, was is further than beauty?, was it something in her nature about her freedom of life, so that she could really have a spontaneous joy in experiencing life?, and you begin to see that it’s the connection with youth. The rebirth happens with Bob. And then she falls into drug addiction. So there are all these dimensions. And the relationship with Tcheky, the detective. This whole idea of being bound together in this activity, the whole idea of coming from a gross American criminality to having the flair of the American, taking the best of the exaggeration from a European mind of what American criminality is, to the sophistication and suave of the European. The old combining of the Henry Miller, the innocence of America, the brashness, with the old World decadence. The old world and the new combined, creating this expatriate guy. The modest dimensions of not having to be one-dimensional, all good, which is the Hollywood mainstream thing.’

Your character undergoes an astonishing physical and mental transformation during the course of the film.

‘It’s always good to have breadth to your role, a realisation or a growth or something. And let circumstances bring you to it. You don’t have to manufacture it yourself, if you’re willing to let go enough and if it’s good writing it will do it. You don’t have to act so much doing Tennessee Williams, it’s in there. It’s just a matter of grasping his syntax and his rhythm. Early on I used to write all the plays out long-hand, because I wanted to ponder the words long enough. I knew if I just read it, I wouldn’t focus on it enough. So I would go back through the process the writer had to. Handwriting the stuff took forever!’

There’s a gentlemanly quality to Bob, a charm that is very seductive.

‘That’s Bob’s concept of civility. He also has this discipline of respect. In order to be a gambler discipline is the requirement. Gamblers tend to have irreverence towards money. Yet when you see them play, they manage money real well. But they also have a non-social concept of money. They don’t care if they lose it – it’s the game, the process, where the experience is. What they’re after is getting out of the rut of living on memory and live instead on the moment- they propel themselves onto a game where they are going to lose it all because they become alive. It’s the same thing with the heist. Eventually that’s what the theme of the film espouses – to live passionately with life. Bob actually says, ‘Play the game to the limit and damn the consequences.’ If you play it, without holding back, and pull out the stops then you’re totally involved. You couldn’t have a more fuller time. You’re fully engaged. The difficulty with this whole thing is that out of trying to achieve a sense of security, we lose the spontaneity of life. We desperately want to have something be permanent, because we’re not. And yet we immediately become alive once we accept the impermanence. It could go. It’s our last moment, so right now becomes important. You don’t take things for granted. You don’t dismiss trees as trees; all of a sudden they are a living thing. I see people reach out and rip leaves off trees. They are doing that because that is not life, the only thing in life they identify with is the way they live. I was one of those people one time too. I have a relationship with plants. I now acknowledge the fact that plants are alive and I am intricately bound to them. I have a garden I¹ve had for thirty years.’

As a remake of Bob Le Flambeur, The Good Thief belongs to a tradition of caper movies. Why are films about con-artists and heists so enduringly popular?

Well I think The Good Thief is questioning the basic nature of reality. You have the fake and the real robberies, and the fake is just as real as the real. The basic nature of life is arbitrarily deciding what is real. It’s a consensus deal, and the minute you behave outside the consensus, you’re a subculture, a bohemian or something else. Reality is far beyond what our self believes. Our self is about stacking up experiences and memories. But by storing a memory you alter it. It’s great fun to alter those things, because the base story of who you are becomes this fantastical lie.

Does this then mean that becoming more mature, and having more life experiences has made you a better actor?

‘The thing with experience is that there is a culture that likes to disregard experience. The stacking of experience is what the self is made of. We start out relatively blank with some genetic tendencies. The experience itself activates what the genetics will be: if you don’t activate them, those genetics won’t really come through. The whole idea of self is a slow-building process through life. We have certain experiences that disintegrate the whole self. We have these breaks, which I could tell you are periodic and cyclical. A reorganization every seven years, where consciousness has to make a whole shift. These breaks are painful, because we lose our grips and we get shaky. That’s the great pattern of life, that vulnerability. Learning takes place when there is some kind of threat. Optimum learning has to have an element of life threatening in it. Not so much that we stay stressed constantly, because then the cortical overwhelms us but enough stress that we’re propelled to figure out a way to survive. Then our dendrites increase tremendously.

There was a famous experiment with three mice – one they gave everything, the other one they gave everything but he had to run round the wheel, the third one they took him out once or twice a week and they put him in a maze, which they changed all the time. They stressed him. After three months they did a brain scan of all of them, and looked at dendrite growth. The mouse that had had everything didn’t grow anything, the mouse that ran grew dendrites but he didn’t hook them up. The mouse that was stressed, he grew tremendous dendrites and he hooked them on. Learning is about having a bit of a life threatening element in it. You have the old saying, ‘You don’t learn anything in school. You learn it in life’ That’s true.’

Talking of learning, you were acting opposite a very inexperienced actress Nutsa Kukhianidze, playing an incredibly nonchalant and world-

weary teenager. What was it like to act opposite her?

‘Nutsa is on this free wheeling, floating of life. Where it comes from is mysterious. She’s from Georgia and she doesn’t talk about her past much. You get little sketches of it though and everybody fantasizes about who she is, and one of them is that she is a princess. Wherever she comes from, that is her basic quality. Neil saw this immediately and allowed her to be in her own rhythm, which is absolutely right for this character. She never falters. What you’re sensing is truly there. It’s marvellous, it’s magical, it’s her personal charisma. Bob as on older person is more studied. I talked to her not long ago about her last film, and she said, ‘It was hard work. I had to act’. Not like this one. Whoever Neil chose for that role had to be that role. He looked around a lot. He was looking specifically for what he had in mind. It was a rare find.’

James Coburn passed away recently. What was it like to work with him and Paul Schrader on Affliction?

‘I didn’t know James before that film. I met him during rehearsals. James wanted to do that role, so you had an older actor who was enthusiastic about it. Schrader had told me he was going to do this, but I didn’t think he was going to do it this way. He was worried about older actors bringing to the table old roles. He wanted something new. Schrader told James that he didn’t want him to use his trademark voice – if he said that to a younger actor, the guy would have taken it personally and said ‘He doesn’t want me to use my voice’. Right away we sunk into those two relationships. He understood the book. That was an interesting thing. Paul and I had been working on it for five years. When he got it financed, I said yes to it right away when I read the screenplay. A year went by before he raised the money, and I was busy with another project. I also didn’t feel I was ready to do the role in Affliction. There was an area I didn’t get, which was the novelist Russell Banks talking about not only the inheritance of this thing passed on, but being passed on from a very pre-historic time, back in cave time. It had to have this tremendous feel of abstract weight to it. It took me five years. I called Paul immediately, and said, ‘I hope you’re not terribly angry with me’. A lot of the story is in the Willem Dafoe character’s refusal to confront his brother Wade in any way. We had gone to Paul Newman first, and he had said that he didn’t think his audience would accept him in that way. James was right for that role, and it was something that he wanted for a long time. Pure acting, pure character, pure submersion.’

Related:

Nick Nolte interview from The Spiderwick

Last modified on